Understanding Counterparty Risk Remains Essential In The Argentine Renewable Framework

Cecilia Fullone

Directora, S&P Global Ratings

The Republic of Argentina has stepped up plans to restructure its power markets to incorporate more renewable energy sources. The government’s goal is for renewables to represent roughly half of all new power generation capacity within 10 years. Considering the currently very narrow gap between peak-time energy supply and demand and an environment vulnerable to climate change,  S&P Global Ratings believes Argentina is on the road to address the potential and need for a stronger renewable energy industry to support economic growth over the next decade. Nevertheless, the road could be bumpy given the country’s past default record. Long term, the credit strength of the country’s renewable energy projects depends on a well-established predictable and transparent regulatory system. For the plan to substantially increase renewable energy resources, Argentina will also need to create a regulatory apparatus that’s more investor-friendly. If the framework has large gaps or isn’t clear, investors will likely to shy away from renewable energy projects because of the potentially weak risk-return tradeoff. The renewable sector is growing fast, resulting in increased demand for ratings on related projects. In this light, we’ve outlined some of the key issues we would consider when assessing renewable project financing in Argentina. We’ve specifically focused on wind and solar energy projects, which currently represent 98% of the recent projects awarded. Moreover, we focus on counterparty risk to address a number of the questions we’ve recently received from market participants.

S&P Global Ratings believes Argentina is on the road to address the potential and need for a stronger renewable energy industry to support economic growth over the next decade. Nevertheless, the road could be bumpy given the country’s past default record. Long term, the credit strength of the country’s renewable energy projects depends on a well-established predictable and transparent regulatory system. For the plan to substantially increase renewable energy resources, Argentina will also need to create a regulatory apparatus that’s more investor-friendly. If the framework has large gaps or isn’t clear, investors will likely to shy away from renewable energy projects because of the potentially weak risk-return tradeoff. The renewable sector is growing fast, resulting in increased demand for ratings on related projects. In this light, we’ve outlined some of the key issues we would consider when assessing renewable project financing in Argentina. We’ve specifically focused on wind and solar energy projects, which currently represent 98% of the recent projects awarded. Moreover, we focus on counterparty risk to address a number of the questions we’ve recently received from market participants.

Overview

– Argentina aims to diversify its energy mix as well as to mitigate climate change. – The government’s goal is to invest $15 billion in renewable energy projects, with a target of 10,000 megawatts by 2025. – The country’s renewable program includes support mechanisms to foster investments amid the still-weak institutional environment. – The credit quality of Argentina’s energy sector remains fragile and limited by offtakers’ creditworthiness. Argentina plans to invest $15 billion in renewable sources to reach the ambitious target of 20% of its energy mix—or around 10,000 megawatts (MW) compared with the current 800 MW base—by 2025. Although Argentina designed its new contractual renewable energy framework to lower project risk and overcome the investment barriers that haunted previous government attempts, we don’t think it would be enough to delink a project from the sovereign’s weak creditworthiness. We believe the longterm credit strength of renewable energy projects depends on a predictable and transparent regulatory system that is sustainable over a long period. And, although the bidding process for renewable energy started off well in 2016, we still have doubts regarding the energy collection process and offtaker risk, which, in the end, could hurt each project’s credit quality. Argentina’s wholesale power market administrator and clearinghouse Compañía Administradora del Mercado Eléctrico Mayorista S.A. (CAMMESA) acts as offtaker. The entity has a track record of delaying payments to the market players because of the system continuous deficits. Although we don’t rate CAMMESA, we believe its credit quality could be similar to that of Argentina (B-/Stable/–). As a result, we think that for all projects, the offtaker counterparty risk will limit each project’s credit quality.

Argentina Needs To Increase Its Power Capacity As Soon As Possible

The Argentine power and energy sectors must increase capacity to cover unsatisfied demand at peak times, and significant investments are needed to meet that challenge. Key characteristics of the country’s power market include increasing demand for electric power, coupled with aging, inefficient generating capacity, and high operating costs. Together, these elements have narrowed the gap between supply and demand, requiring Argentina to import electricity from neighboring countries and program blackouts for certain residential areas and industries. Also, Argentina’s wholesale electricity prices had been low and distorted since 2001, when Argentina declared itself in default and experienced a large currency devaluation, which discouraged private investment in power generation. In this context, in 2016 and 2017, the new administration substantially increased tariffs and called for bidding processes for new power capacity, including renewables, with the aim of diversifying its energy matrix, while benefiting from the use of clean energies. According to the Ministry of Energy and Mines (MINEM), Argentina needs to incorporate 10 GW of generating capacity from conventional energy sources and 10 GW ofgenerating capacity from renewable sources to meet increasing demand over the next 10 years.

Argentina’s Renewable Energy Targets Are Ambitious

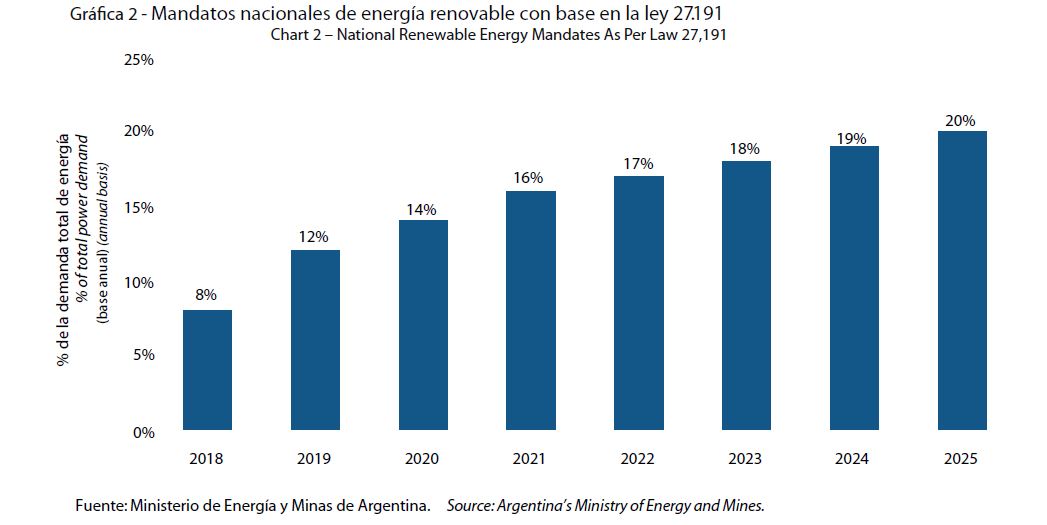

In late 2015, the government passed the Renewable Energy Act 27,191, establishing the basis for a new promotional legal framework, highlighting its effort to advance renewable energy. We consider the targets to increase renewable energy ambitious for the short, mid, and long terms. To reach the 20% target by 2025, installed renewable generation capacity must increase to 10,000 MW from a current base of only 800 MW. In other words, renewables are set to represent roughly half of all new power generation capacity over the next decade. As a first step to comply with the Renewable Energy Act 27,191, the government launched RenovAR in May 2016. RenovAR is a public tendering program, which provides for certain fiscal incentives and financial support mechanisms, along with regulatory and contractual enhancements aimed at boosting investments in the renewable arena. Under round 1 and round 1.5 of RenovAR, both launched in the second half of 2016, the government has received offers for 6.4 GW of new renewables generation capacity, multiple times its original expectation, and has awarded contracts totaling 2.4 GW—equivalent to around $3 billion—to 59 clean energy projects. The government will continue to promote the installation of renewable generation by implementing successive rounds of the RenovAR program starting in 2017. In addition, in the second quarter of this year, the government will release detailed regulations on the private power-purchase agreement (PPA) market and self-generation, applicable for wholesale market users with annual demand in excess of an average of 300 kilowatts.

The Government Has To Overcome Previous Failed Attempts To Boost Renewable Investment

RenovAR’s contractual framework rests on two agreements that work in tandem to provide the elements that are customary in a typical renewable energy PPA. Both agreements are subject to Argentine law and include the possibility of international arbitration. Companies that are awarded projects enter into a 20-year PPA with CAMMESA, which acts as offtaker on behalf of distribution utilities and large wholesale market users. Pursuant to the PPA, project companies assume the obligation to construct and reach operations within a timeframe set by each bidder in its proposal, generally ranging between 13 and 30 months. Electricity generated by the power plant is paid for at the awarded price (for current projects about US$56/MW for wind, and US$60/ MW for solar) and adjusted annually by a minimum fixed annual adjustment of 1.7% that could increase for projects reaching commercial operations before the 24-month maximum term set forth in RenovAR’s contractual framework. Project companies have the obligation to provide a minimum amount of electricity on an annual basis and deficiencies are subject to make-up periods and/ or penalties. Along with the PPA, the government created a support mechanism to provide project companies with guarantees that enhance the legal framework under Argentina’s current—and still weak—market conditions. The monthly payments under the PPA will be guaranteed by Fondo Fiduciario de Energia Electrica (known as FODER), which will have a single, segregated 12-month  reserve account to support monthly invoice payments to generators. In addition, the bidders may opt to contract a limited and conditional guarantee from the World Bank. Projects will be financed with a combination of equity and debt, through bank loans. A few companies, such as Pampa Energia S.A. (B-/Stable/–) and Genneia S.A. (not rated), have recently issued bonds in the international markets partly to fund the construction of the awarded wind farms, neither of them done through a project finance mechanism. We believe that to meet demand and exploit potential export opportunities, Argentina will need foreign investments that tap the bank and capital markets for funding. Yet, in our view, the country’s credibility and reliability is still weak and needs institutional improvements such as a stronger rule of law and a more independent judicial system in order to improve relations with global and local investors. In addition, Argentina’s economy has experienced significant volatility over the past decade, including low growth or contraction, high inflation, and currency devaluation, all of which impairs incentive to invest in the country. We believe the country’s credibility will take some time to repair, particularly in terms of restoring a payment culture in light of Argentina defaulting in the past 15 years.

reserve account to support monthly invoice payments to generators. In addition, the bidders may opt to contract a limited and conditional guarantee from the World Bank. Projects will be financed with a combination of equity and debt, through bank loans. A few companies, such as Pampa Energia S.A. (B-/Stable/–) and Genneia S.A. (not rated), have recently issued bonds in the international markets partly to fund the construction of the awarded wind farms, neither of them done through a project finance mechanism. We believe that to meet demand and exploit potential export opportunities, Argentina will need foreign investments that tap the bank and capital markets for funding. Yet, in our view, the country’s credibility and reliability is still weak and needs institutional improvements such as a stronger rule of law and a more independent judicial system in order to improve relations with global and local investors. In addition, Argentina’s economy has experienced significant volatility over the past decade, including low growth or contraction, high inflation, and currency devaluation, all of which impairs incentive to invest in the country. We believe the country’s credibility will take some time to repair, particularly in terms of restoring a payment culture in light of Argentina defaulting in the past 15 years.

Counterparty Risk: Still Not Mitigated

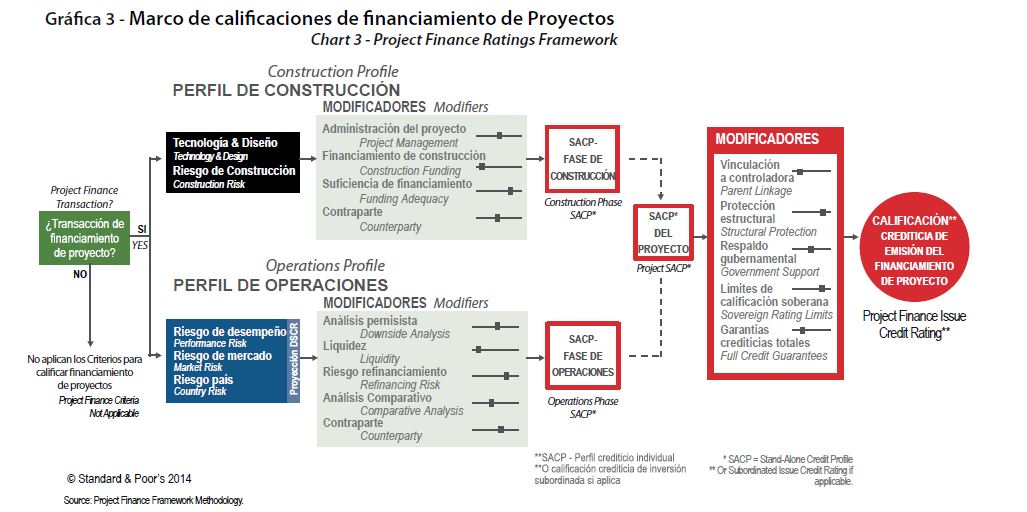

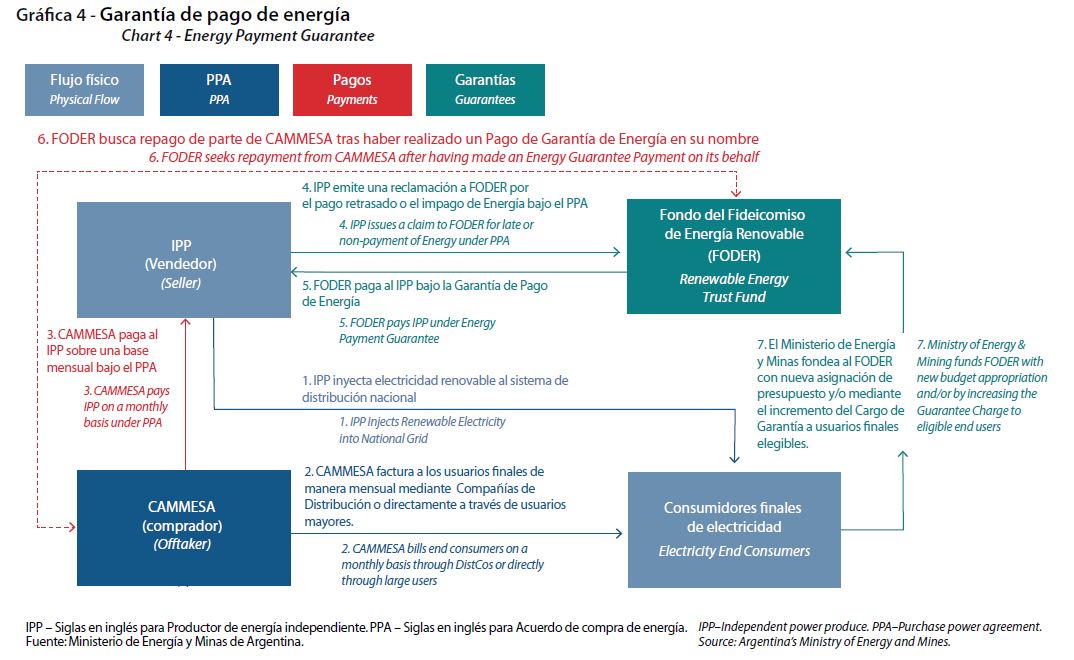

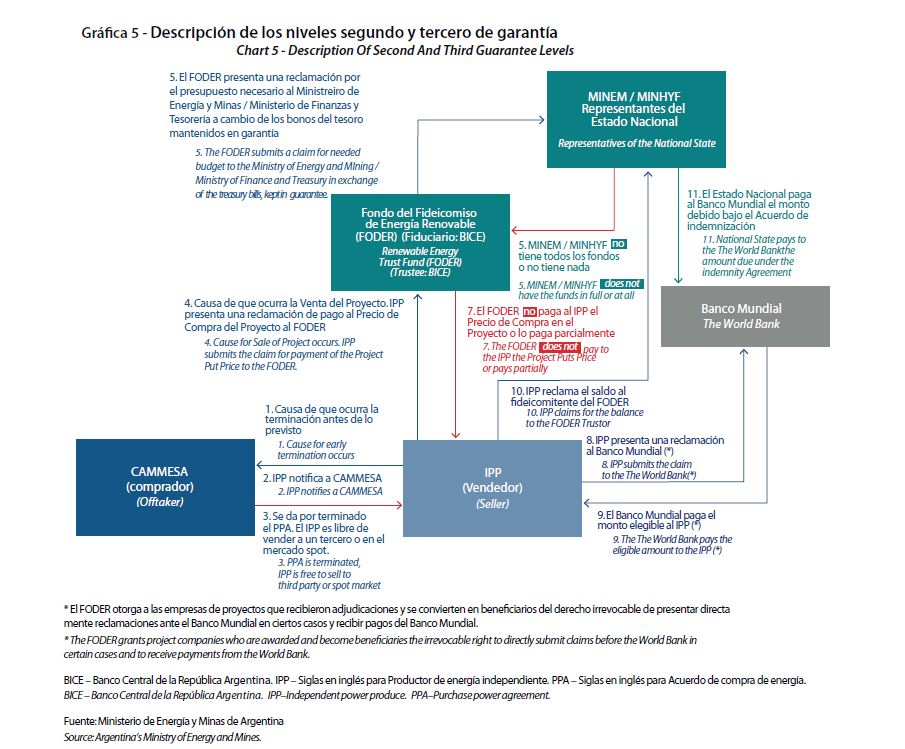

If we were to analyze a RenovAR project under our Project Finance Methodology, we would likely conclude that the project’s energy offtaker would limit its creditworthiness. The key steps in our project finance rating process are summarized in chart 3. First, we establish a project’s stand-alone credit profile (SACP), which is an assessment of its intrinsic creditworthiness. The SACP is the lower of our assessments of the project’s construction phase SACP and operations phase SACP. To arrive at the final rating, we adjust this project SACP according to our assessment of factors related to the transaction structure, extraordinary government support, relevant sovereign ratings, and any full credit guarantee, if there is one. For most of the renewable projects we rate, we don’t see construction as the primary risk and our main consideration for assessing projects under RenovAR would probably be operations. We typically consider photovoltaic solar and onshore wind projects as relatively simple in terms of construction. In addition, we expect most of the projects to complete construction within the next two years–that is, within the current administration’s term in office–thus narrowing the risk of sudden policy or macroeconomic changes. Regarding operations, we believe that an offtaker’s creditworthiness could limit a project’s rating. Our counterparty revenue risk analysis is key to forecasting expected cash flows for the term of the project finance debt. Our criteria sets out a three-step process in assessing how risks posed by revenue offtakers could constrain the issue-level rating on a project: – Identify the material counterparties. Material counterparties are those that significantly affect the timeframe or cash available to service debt.  In the case of RenovAR projects, we consider CAMMESA as a material counterparty because it will govern all, or substantially all, of a project’s revenues. – Determine the replaceability or irreplaceability of material counterparties. We would likely treat CAMMESA as an irreplaceable counterparty because without its support there is no market for a project’s output. Although the project might sell the energy in the spot market, the price may be lower. – Determine the counterparty dependency assessment (CDA). For irreplaceable counterparties, the CDA is linked to the rating on the counterparties. We could consider raising a rating when the service is regulated or essential and there are regulatory or legal support of payments. Although we don’t have a rating on CAMMESA, we believe its credit quality would be closely linked to the one of Argentina (B-/ Stable/–). In addition, the criteria allows for a two-notch uplift in cases where there is regulatory and legal precedent to support payments. However, in the case of CAMMESA and although renewable energy PPAs are senior to most other payments in the wholesale market by law, the entity has a track record of delaying payments to the market players because of the system continuous deficits. As a result, we consider that for RenovAR, the offtaker counterparty will limit the projects’ credit quality. Even though the program includes a three-level guarantee, they’re not sufficient to disregard counterparty risk completely, as we assess those relevant for the recovery standpoint, but does not fully address the timely payment. CAMMESA has the primary obligation to pay for electricity on a monthly basis by using the available funds it holds from regular collections and/or transfers from the government. If CAMMESA is unable to pay in full for the electricity on the due date, FODER backstops CAMMESA by using funds that are kept in its “energy payment guarantee account,” which the Ministry of Energy and Mines funds from a specially preapproved budget. The second-level guarantee consists of an option that project companies hold to terminate the PPA when neither CAMMESA nor FODER pays for the energy delivered after four consecutive months or six nonconsecutive months within any 12-month period. In that case, the project company could keep the power plant and eventually sell the energy in the spot market, potentially resulting in lower revenues and probably hampering the project’s ability to service debt obligations. Alternatively, the project company could transfer the project assets to FODER and receive cash compensation. If FODER doesn’t provide the funds to pay the assets, RenovAR is further strengthened by an additional US$500 million guarantee provided by the World Bank. However, we would only consider those guarantees for our recovery analysis, which estimate the percentage of principal and accrued interest due at the point of a hypothetical default on a company’s debt instruments that can be recovered following its emergence from a hypothetical bankruptcy. In our view, the long-term credit strength of renewable energy projects depends on a predictable and transparent regulatory system that is sustainable over a long period. We believe Argentina has good solar and wind resources, demand for power growing at least 3% per year, and a need to revamp on outdated power system. Nevertheless, the essential ingredient to make the country’s plan for increasing renewable energy resources a reality would be to continue making its regulatory apparatus more investor-friendly. If the regulatory framework is not clear and cannot provide investors with long-term legal certainty, characterized by an adequate track record, the projects’ credit quality will be weak.

In the case of RenovAR projects, we consider CAMMESA as a material counterparty because it will govern all, or substantially all, of a project’s revenues. – Determine the replaceability or irreplaceability of material counterparties. We would likely treat CAMMESA as an irreplaceable counterparty because without its support there is no market for a project’s output. Although the project might sell the energy in the spot market, the price may be lower. – Determine the counterparty dependency assessment (CDA). For irreplaceable counterparties, the CDA is linked to the rating on the counterparties. We could consider raising a rating when the service is regulated or essential and there are regulatory or legal support of payments. Although we don’t have a rating on CAMMESA, we believe its credit quality would be closely linked to the one of Argentina (B-/ Stable/–). In addition, the criteria allows for a two-notch uplift in cases where there is regulatory and legal precedent to support payments. However, in the case of CAMMESA and although renewable energy PPAs are senior to most other payments in the wholesale market by law, the entity has a track record of delaying payments to the market players because of the system continuous deficits. As a result, we consider that for RenovAR, the offtaker counterparty will limit the projects’ credit quality. Even though the program includes a three-level guarantee, they’re not sufficient to disregard counterparty risk completely, as we assess those relevant for the recovery standpoint, but does not fully address the timely payment. CAMMESA has the primary obligation to pay for electricity on a monthly basis by using the available funds it holds from regular collections and/or transfers from the government. If CAMMESA is unable to pay in full for the electricity on the due date, FODER backstops CAMMESA by using funds that are kept in its “energy payment guarantee account,” which the Ministry of Energy and Mines funds from a specially preapproved budget. The second-level guarantee consists of an option that project companies hold to terminate the PPA when neither CAMMESA nor FODER pays for the energy delivered after four consecutive months or six nonconsecutive months within any 12-month period. In that case, the project company could keep the power plant and eventually sell the energy in the spot market, potentially resulting in lower revenues and probably hampering the project’s ability to service debt obligations. Alternatively, the project company could transfer the project assets to FODER and receive cash compensation. If FODER doesn’t provide the funds to pay the assets, RenovAR is further strengthened by an additional US$500 million guarantee provided by the World Bank. However, we would only consider those guarantees for our recovery analysis, which estimate the percentage of principal and accrued interest due at the point of a hypothetical default on a company’s debt instruments that can be recovered following its emergence from a hypothetical bankruptcy. In our view, the long-term credit strength of renewable energy projects depends on a predictable and transparent regulatory system that is sustainable over a long period. We believe Argentina has good solar and wind resources, demand for power growing at least 3% per year, and a need to revamp on outdated power system. Nevertheless, the essential ingredient to make the country’s plan for increasing renewable energy resources a reality would be to continue making its regulatory apparatus more investor-friendly. If the regulatory framework is not clear and cannot provide investors with long-term legal certainty, characterized by an adequate track record, the projects’ credit quality will be weak.